Image credit: Pastor Michael Weaver

Colonel Sanders had his secret recipe. The Academy Awards have their lockbox and their security detail.

And the Lutheran Church Women of North Carolina had their hundreds of zipped-mouth accomplices who were not about to let this cat out of the bag. And they didn’t.

The ringleader labeled this project “top secret.” Phone calls crisscrossed the state. Handwritten letters and detailed instructions arrived in the mail, complete with stamps and envelopes in days long before emails, texts, or even many fax machines. The paper trail was long and risky.

Yet, still, the secret never got out.

The party was public knowledge: at their statewide convention that August of 1978, the North Carolina Lutheran Church Women (NC LCW) would honor outgoing bishop George Whittecar for his 15 years of faithful service as the synod “president,” as the office was then known.

A gift would certainly be appropriate here. But what should it be? A cake? A plaque? Maybe a gift card? (Actually, gift cards weren’t an option. Those now-popular, plastic presents didn’t exist in 1978.)

It was February. The event was six months away. The Rev. Dr. Whittecar had crisscrossed the state many times since his election in 1963. Dr. Whittecar knew his congregations; his congregations knew—and loved—him. This was an occasion that called for something more than a thank-you note.

What if, wondered the women’s group president, we honored Dr. Whittecar with a gift that had the fingerprint of every single congregation in North Carolina? All 210 of them? From the mountains to the coast? Kitty Norris remembered a gift given her own father years earlier when the longtime Gastonia pastor had moved from one congregation to another. Those church members presented their outgoing pastor with a homemade quilt.

Norris’ idea took hold, and the NC Lutheran Church Women—the precursor to today’s Women of the ELCA—quickly set to work on such a gift for Dr. Whittecar. It was an ambitious undertaking, though. One quilt? Representing 210 Lutheran congregations? How?

We’ll give every single congregation a square of cloth, they decided. We’ll stitch them together. Like 66 different books make up one Bible, 210 North Carolina congregations will contribute to one quilt for Dr. Whittecar.

Among the women’s group was a full-time schoolteacher, part-time choir member, part-time Luther League advisor, and summertime Lutheridge co-director—all in the same person. It quickly fell to her, Donna Poovey Cline (later White), to put this quilt concept into reality. Cline wasted no time.

“She spent all her waking hours” on the project, says Ruth Matkins, the eldest of the Whittecars’ three children, who, like her parents in 1978, was none the wiser about the project until its unveiling that August.

Cline’s first task was the necessary brainstorming for symbols that would represent all 210 Lutheran congregations. The elementary schoolteacher and organizer-par-excellence quickly whittled the massive list down to its 110 different church names. There were, for example, nine St. Paul Lutheran Churches in North Carolina at that time (the most of any single name).

From there, Cline dove into researching those church names with all the gusto and expertise of a seminary historian. Each congregation would be represented on the quilt, they decided, by a symbol representing its name, along with its location, and year of origin. No distinctive steeples. No historical nugget from a congregation’s founding. Just its name in symbol form.

Some names lent themselves to artwork more easily than others. For the Resurrection Lutheran Churches in Kings Mountain and (then) Greensboro, Cline chose a butterfly. The synod’s two St. Peter congregations were given the traditional symbol for the apostle: an upside-down cross and the “keys of the kingdom.”

“But what do you do,” wonders Matkins now, “with something like ‘Philadelphia?’ Or ‘First’? Or ‘Jerusalem’?”

The answers reside in the homemade, homework book that Cline put together during the quilt’s construction, sketching each of the 110 designs. On each page of a thick, red-bound binder is a church symbol, complete with Cline’s thoroughly researched reason for choosing that design.

“Bethphage,” headlines one page for the Lutheran congregation outside Lincolnton. “A small village between Jericho and Jerusalem near the Mount of Olives. It was to this place that Jesus sent his disciples to get the donkey upon which he rode at the time of the triumphant entry into Jerusalem.”

Adorning Cline’s sketch page is a simple, smartly drawn donkey. That would be the stitching assignment for the ladies at Bethphage Lutheran Church. At 209 other congregations across the synod, other women got their artwork and their marching orders, and by early spring of 1978, the mailings went out with a 5×5-inch square of white material to each.

The request: return your embroidered or applique contribution within a month. The demand: keep it a secret!

Matkins has it on good authority that women across the state “were thrilled to be able to participate in this project.”

The first finished products came back within a week. The organizers reported that as many as 25 stitched squares would arrive in a single day’s mail delivery. Next step: assemble the 210 squares into one quilt.

In quilting sessions around long tables at Lutheridge, where Cline lived with her husband on staff, she and other women spent hours stitching each individual square onto the massive light-blue background. There, too, Cline had done her homework. With a mother who’d taught math and her own teacher training, Cline had calculated exactly what they’d need for the 210 squares: a canopy 8 feet 4 inches tall and 6 feet 8 inches wide.

“This wasn’t done by machine,” Matkins emphasizes. “It was sewn by hand, and it was all-consuming.”

It wasn’t unusual for others in the know to come to Lutheridge and witness the daily progress, referring to it simply as “the quilt”—and of course keeping the secret.

All these years later, Matkins still marvels at the detail, artwork, and uniformity of each panel.

“To me, it’s just amazing for the beauty of it, for the craftsmanship of it,” she says.

She points to two of the panels stitched by women from the same design—one at Lebanon Lutheran Church in Cleveland, the other at Lebanon in Lexington, known today as The Arbor Lutheran Church. Though both congregations received the same sketch outline for a cedar tree, the needleworkers in each place crafted their own, unique look to the famous “cedars of Lebanon” prized by kings throughout the Old Testament for their aromatic, durable quality.

“Each one of these leaves is a tiny French knot!” Matkins exclaims, pointing to one of the two embroideries that gives the tree leaves a rougher feel. On the other “Lebanon” panel, the congregation’s artists used a smoother satin stitch that gives the cedars a very different look.

Other seamstresses at other congregations made similar, creative distinctions in their applications of Cline’s design.

With 210 panels stitched into place on the 100-by-80-inch backdrop, the NC LCW delivered the nearly finished artwork to volunteers in Dallas, NC, who put the final, loving quilting touches on the secret surprise. It was, of course, hand-delivered, Matkins says. “They wouldn’t put it in the mail!”

Finally, some six months after their plan was hatched, the Lutheran Church Women gathered for their annual convention. On August 19, 1978, the group called Dr. Whittecar to the Lenoir-Rhyne College stage with his wife, Ruth. On cue, the auditorium curtains were parted to reveal the finished quilt, so large that women standing high on stepladders had to hold it aloft above the floor.

“Everybody just gasped,” says Matkins, though she was actually not there for the presentation. “My parents were just floored. It was a total surprise.”

In a newspaper story a week later in The Salisbury Post, Ruth Whittecar told renowned writer Rose Post how she and her husband later spread the quilt out on a bed at home to get their first really good look at its detail.

“We just looked and looked and looked,” Ruth Whittecar said, “and I got up the next morning and looked and looked and looked again.”

The quilt is that way, dazzling a looker with its scale and beauty, and yet drawing one in for a closer view of each detail in those 210 panels. It literally pulls you in, Ruth Matkins says.

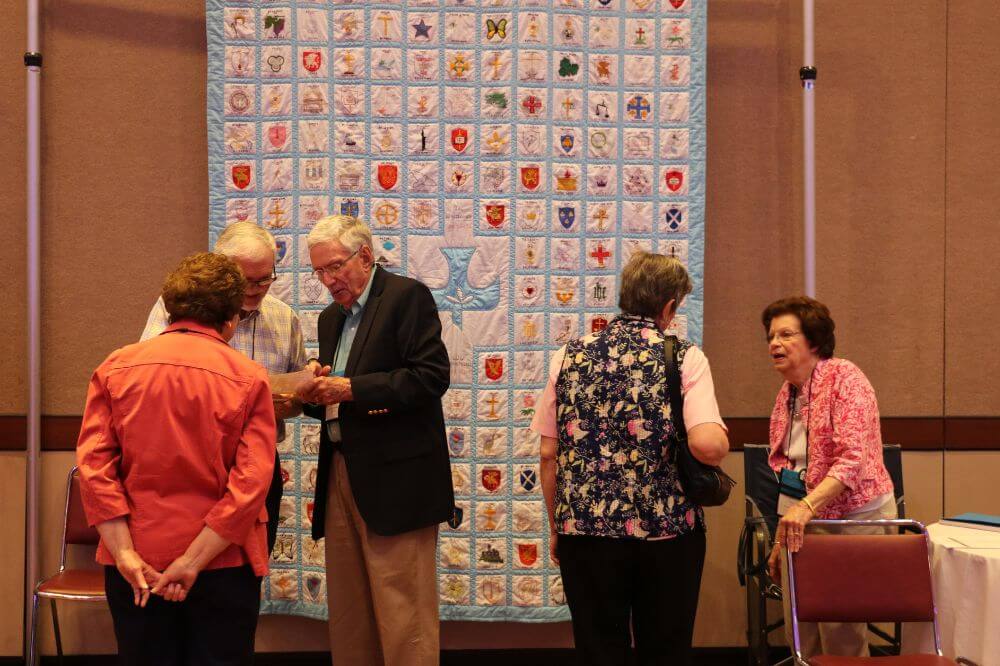

Ironically, though Dr. Whittecar’s gift has traveled the state these past 46 years and been shown occasionally at congregations and quilt shows, and at the 2023 NC Synod Assembly, its sheer size has kept it from finding a permanent home. Matkins and the synod office are on a mission now to give it that home, so that others may appreciate its artistry, its 210 individual stories, and its overriding single message.

“The more you look at it, the more you see,” Matkins says, repeating something she often heard her mother say.

It is indeed difficult to move one’s eyes, panel by panel, past the Holy Trinitys and St. Pauls, from Wittenberg to several St. Andrews and many more, and not imagine the histories and the people and the stories behind each panel. From so many simple 5×5-inch panels come testimonies of faith and connection that onlookers can almost hear whispered out loud.

Matkins has watched over the quilt since her father died in 1984 and her mother in 2003. She’s more than ready to give it a permanent home where others who’ve never seen it or even known about it might view and appreciate it.

It’s a “labor of love,” one first-time viewer said recently. And Matkins responded: “That’s the way mother and daddy saw it.”

Story Attribution:

The Rev. Michael Weaver for the NC Synod